When I was at school, a long, long time ago, one of my favourite subjects was History. But for me, the older the history the better – the World Wars and the Russian Revolution, the agricultural and industrial revolutions, these were all very well, but what I really wanted to study was the dawn of history, and beyond – into prehistory.

When I took Sixth Year Studies History, I had a choice of several topics. It wasn’t much of a choice for me, though. I was immediately drawn to “Northern Britain from the Iron Age to the Vikings”, and from the moment I started the course until the day I left, I had this book checked out from the school library:

W. Douglas Simpson’s book The Ancient Stones of Scotland is fantastic. It’s probably dated in terms of its archaeological detail now, but its sweep of Scottish history told in its stone monuments and buildings from Skara Brae through the Pictish Stones right up to mediaeval castles fascinated me.

And no chapter fascinated me more than Chapter VI, The Brochs and their Builders.

The chapter begins:

“With the brochs, Scottish prehistoric archaeology reaches its climax. They are unique in all the world.”

And they are! There’s nothing quite like them anywhere else, but in Scotland they were tremendously successful, spreading from Orkney and Shetland across to the Western Isles and down through Caithness, with even a few scattered across the lowlands and borders. They bear all the hallmarks of a single point of invention, and an explosion outwards as people saw their neighbours build one and decided that they just had to keep up with the Joneses.

They date from the 1st centuries BC and AD; some have tried to tie their invention into a response to the Roman invasions, but it’s not clear whether the dates line up – and the highest concentration of brochs is furthest away from where the legions of Rome were operating. Perhaps we’ll never know just why they were built – but they’re certainly imposing structures, a statement of power if nothing else.

Most brochs today are ruins barely more than knee height, but there are some exceptions.

The Broch of Mousa in Shetland is nearly complete, standing over 13 metres tall. It’s not actually one of the biggest brochs – its diameter is a lot smaller than most, and its walls are thicker, making its interior even smaller. But these features may well have contributed to its amazing survival.

Dun Carloway broch, on the Isle of Lewis, isn’t as well preserved as Mousa, but is fascinating for another reason – because of the asymmetric collapse, you can see the double-walls with their galleries. The stairs that led to the higher levels were actually inside these walls.

These ruins are all well and good (I love a good ruin!) but wouldn’t it be fantastic to see a broch in perfect repair? Those excellent folks at the Caithness Broch Project certainly think so! Their long-term goal is to build their own broch using drystone techniques; and in the meantime, they’re doing everything in their power to promote and preserve the hundreds of broch sites around Caithness.

If you like what they do, you can become a member to support their efforts for £10 a year – I’ve already joined, of course.

It’s great to see people being so enthusiastic about these fantastic structures. They’ve featured in fiction, too.

Mollie Hunter’s book The Stronghold is her take on how the brochs came to be – with one genius architect in Orkney, trying to find a way to defend his people against Roman slave ships, fighting against clan politics, the opposition of the druids, and traitors in their own midst. It’s a fantastic book, and isn’t lessened by the current archaeological consensus that the invention of the broch pre-dates the Roman invasion.

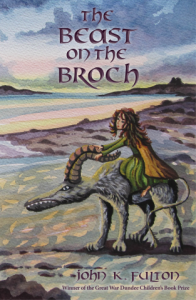

When I came to write my book about the Pictish Beast and the Viking attack on the monastery at Portmahomack, I wanted to have some of the action set out at the point of the Tarbat Ness peninsula – you see, I grew up there, at the lighthouse. But the point seemed awfully bare without the lighthouse tower, so I decided to do the next-best thing – I’d include a broch. Now, there wasn’t actually a broch there, as far as we know, but it’s not too far-fetched, because the Canmore site shows that there is a possible broch site just three miles away at Cnoc Tigh. It’s definitely broch territory!

Of course, my story is set in 799 AD, hundreds of years after the era of the brochs, so the tower had to be a ruin. That was even better for my purposes. Because what better place for a lonely girl to meet a wild mythical beast than on top of a ruined tower? It was the image that came to me as I started to write, and it was the image I kept in my head across dozens of revisions and two years of work.

The Beast on the Broch

The Beast on the Broch is an historical fantasy adventure for children aged 8-12, featuring Picts, Scots, Vikings, a lonely girl, and her unforgettable friendship with the mythical Pictish Beast.

The Beast on the Broch is an historical fantasy adventure for children aged 8-12, featuring Picts, Scots, Vikings, a lonely girl, and her unforgettable friendship with the mythical Pictish Beast.

Available to order now from your local bookshop, in selected branches of Waterstones throughout Scotland, or online from Amazon, Wordery, and so on.

For more information, see My Books.