It was announced earlier this evening that Rosie Rowell and her editor Emily Thomas had won the Branford Boase award for Leopold Blue. This is an interesting book prize, in that it celebrates the editor of the book as well as the writer, and recognises that publishing a book is a collaborative process.

So it seems appropriate to put some thoughts down on the editing process that I’ve just gone through with The Wreck of the Argyll. At the lunch after the award ceremony, I met Helen Sedgwick from Cargo Publishing, and she told me that she’d be my editor. (She’s also the joint MD of Cargo, a freelance editor, a novelist, and has been the editor of a literary magazine – I’m glad I didn’t know all this at the time, as I think I’d have been a bit intimidated…)

A few weeks after I got back from Dundee, I was wandering around the children’s section of Waterstone’s in Leicester (this is not an uncommon occurrence on a Saturday morning for me) when I checked my phone and there was an email from Helen. I have to admit, I was pretty nervous reading that email – what if she hated it? What if she thought I needed to rewrite the whole thing? The last bit of feedback I’d got from a professional had been that I should delete the entire Harry Melville plot – half the book.

I needn’t have worried. Helen had plenty of comments, but to my relief none of them said “rewrite the book”. Helen gave me several paragraphs of comments – details of places where she thought I needed to do some work: fleshing out the character of the bad guy, making the details of the plot more obvious and less hand-wavy, and so on.

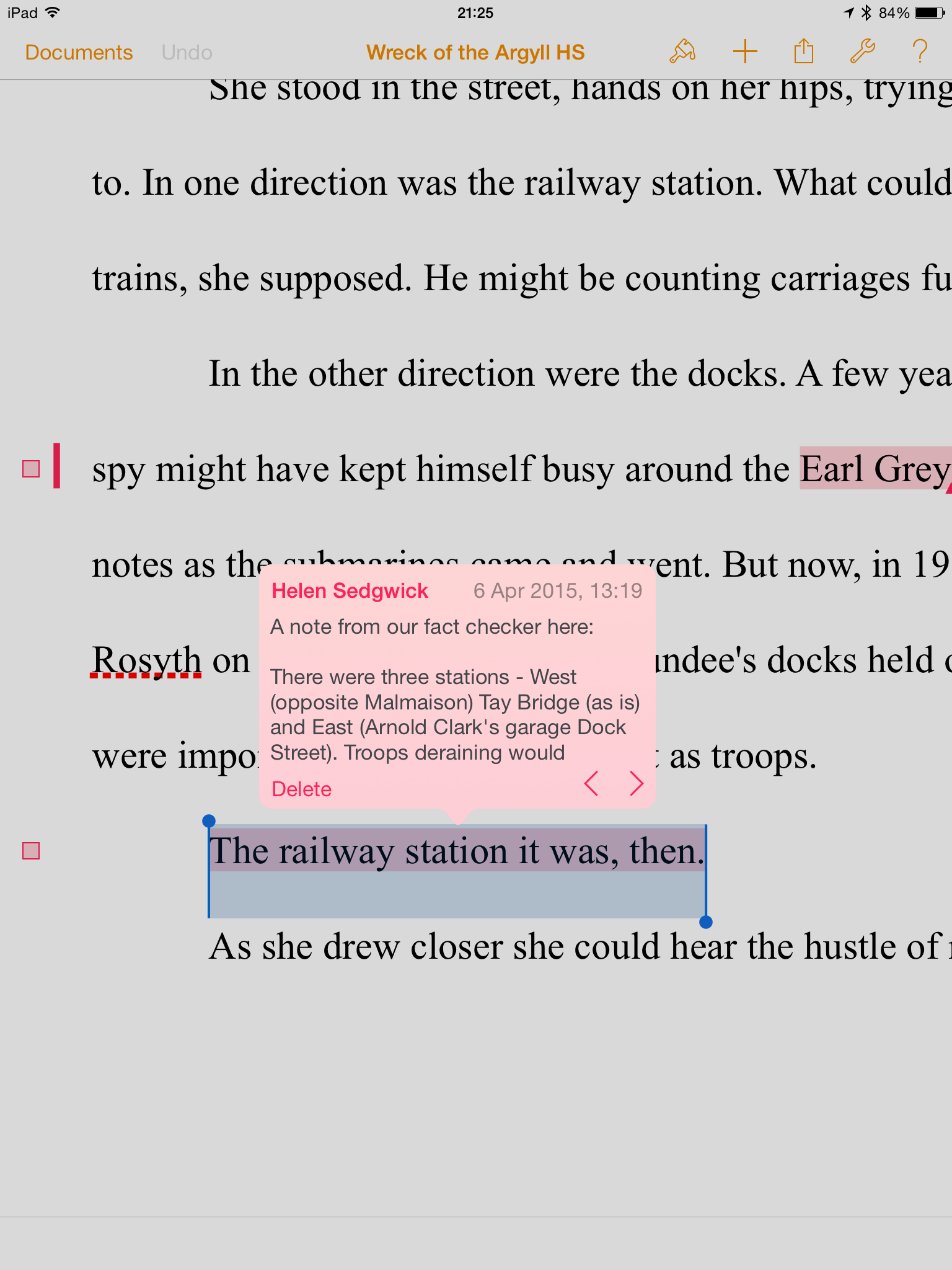

She’d also provided an updated and annotated Word document. She’d made changes throughout the document, with tracked changes so I could review each one and either accept or reject them. Mixed in with these changes were comment boxes where she thought I should expand on something, or cut something down, or (and this was particularly exciting for me) where the fact checker had a question or a comment.

How great is that? I’d done my best with the historical accuracy, but I’m an expert neither on Dundee nor on the First World War, so the safety net of having someone do a thorough job on the history and geography was fantastic. Fortunately, I hadn’t made too many howlers, and I could deal with most comments with an extra word or two for clarification.

Another thing that Helen pointed out was my over-use of “dark” and “mountainous seas” when describing the Argyll‘s stormy voyage through the night, and suggested a bit of variation. Here, Helen was extremely helpful – not only did she point out where I needed to make changes, she gave me plenty of suggestions about what sort of things I could try. One thing I’m not particularly good at is engaging all the senses with my writing – Helen suggested using the smell and taste and feel of the darkness, the prick of salt against the eyelids, fingers numb from gripping the rails… It was all extremely useful and inspiring stuff, and when I got her email of suggestions I couldn’t wait to get home and get on with the work.

After about a week of editing, I’d gone through all of Helen’s comments. I’d addressed each comment box as well as I could, and reviewed every tracked change she’d made. Every tracked change, I looked at, pondered, then accepted. Every single one. There were many changes where I nodded and wondered how I could have been so stupid, others when I exclaimed “of course!” and a few where I thought grudgingly “OK, I suppose that’s a bit better than what I wrote.” There was one single change that I rejected. Then I thought about it. And thought about it a bit more. Then realised Helen was right, and put the change into the document.

It’s quite hard, as a writer, to accept that someone else has better ideas about your words, and I suppose my attempted rejection of that one change was a stab at showing a bit of ego and independence.

But in my day job, I do a lot of the work of an editor, anyway. As a technical author, I frequently have to take the raw information provided by programmers and managers and turn it into consistent, grammatical English. I don’t even give them the option of accepting or rejecting my changes – I’m the expert, so they just have to accept that my word is law when it comes to technical documents.

For fiction, I’m not an expert. Until September 25th, I’m still an unpublished author. So I didn’t have much difficulty accepting Helen’s edits.

I’m sure it would have been more difficult if she’d asked me to chop out half the book and rewrite the other half, of course. But fortunately it didn’t come to that.

I sent Helen my changes and waited.

Five or six weeks later, I got another annotated document back from Helen. I opened it with a certain amount of trepidation. Had my edits been OK? Had I found enough synonyms for “dark mountainous seas”? Had I introduced any more errors with my amateur changes?

Fortunately, this time the changes were minimal, and I managed to get through them in a couple of hours. Helen had another couple of tasks for me, though. Could I come up with a blurb for the back of the book? And maybe a few words for an “about the author” page?

Writing a book is hard. Writing a synopsis – a 1- or 2-page summary – is harder. Coming up with about a hundred words that describe your book in a way that’s hopefully intriguing enough to make someone buy it? That’s really hard!

Still, I gave it a go, and I think it’s an OK attempt.

All writing tasks done, there was just one more stage. Helen sent me a PDF of the typeset final proof for one last check, along with a couple of last-minute questions. I read through the whole thing (it looked like a book! a real book!) and passed on my final comments.

Helen was happy with the final changes; she made the last few corrections and said that we were ready to go to print. Now that was an exciting email.

From start to finish, the editing process took three months. This is very quick for the publishing business – but I suppose it’s been driven by the fixed date of September 25th for the publication. Competitions tend to result in accelerated publication schedules – I’ve heard of authors who’ve had to wait up to two years after acceptance for the book to see print, so I’ve been very lucky.

Now it’s just under three months until my book is released, and there’s nothing more I can do to it. Except one thing: under no circumstances should I look at the manuscript between now and then. The chances of finding a mistake now it’s too late to do anything about it are too high. Better to live in ignorance than stress about it between now and the end of September.

What do you mean, the city’s not spelled “Dundie”?