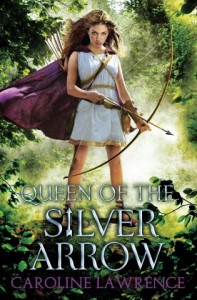

Queen of the Silver Arrow, by Caroline Lawrence, is a retelling of part of Virgil’s Aeneid – the story of Camilla, huntress and warrior, who comes to the aid of Prince Turnus against the invading Trojans, led by Aeneas, who are fleeing the sack of Troy and looking for a new home in Italy.

I love Virgil. When I was in second year in Portree High School, anyone who’d shown a decent level of language ability in first year (in either French or Gaelic) was given the opportunity to take a second language class. The choices were German or Latin – and for me, it was no choice. Mr Nicol, the Latin teacher, had a classroom full of amazing books. Whole shelves of black-spined Penguin Classics. I’d already borrowed Homer’s Iliad from him, and devoured it, and wanted something similar – “Do you have the Aeneid?” I asked. Except I didn’t know how to pronounce Aeneid, only ever having seen it written down, and asked for the AYE-knee-id, rather than the aye-NAY-id.

He let me borrow the book anyway. I loved it. When we got onto reading parts of the poem in the original Latin (I seem to recall the first part we did was Aeneas battling Turnus from right at the end of Book XII) it was a revelation. Through O Grade and Highers, sections of the Aeneid were a constant companion. At St Andrews, studying Classics, the Latin department regularly set several books of the Aeneid as summer reading – and we were tested on them the first week back. I recall vividly sitting at the desk of my summer job one lunchtime, the Latin text in one hand and my C. Day Lewis translation in the other.

It didn’t feel like work at all.

I’m sure I’ve read the whole thing in Latin – although probably not in order.

I’d even put together some notes for a possible YA novel based on the Camilla episode – but Caroline Lawrence has beaten me to it!

And a splendid job she’s done of it, too. There’s not a huge amount in the Aeneid about Camilla – there’s an origin story, told by the goddess Diana to one of her nymphs, how Camilla’s father saved her by tying her to a spear and throwing her across a river; and a long battle scene, where Camilla slaughters the Trojans before being cut down herself. There’s also a little bit of an inconsistency where Camilla is the leader of the Volscians, while elsewhere being described as an exile; Lawrence has filled in the gaps nicely, and even managed to reconcile the contradictions cleverly.

She takes a single mention of Acca, friend and companion of Camilla, “one who had been her confidante and of all her companions was the truest” and makes her the narrator. This allows her to maintain some of the mystery of Camilla – some of the hidden past of the half-wild huntress of the woods. Everything we see of Camilla is through Acca’s eyes. She’s the one who brings Camilla out of the woods and into civilisation, and encourages her to teach Acca and her friends how to become hunters and warriors – occupations normally denied to girls.

This is the perfect mechanism to tell the story and fill in the gaps without having to interpolate too much – Acca doesn’t know everything about Camilla, so it makes sense that she retains her mystery. Telling the story from Camilla’s viewpoint (which would have been my instinct) would require an awful lot of making stuff up – and the danger when interpolating into an existing story is that the reader will see the joins.

There are no joins here – the story works brilliantly and coherently as a tragic adventure.

Because the story is tragic – the Aeneid is the tale of Aeneas, whose descendants will be the founders of Rome, and Camilla is on the wrong side of that battle. She dies in battle – heroically, but horribly, having forgotten her own advice about a warrior needing the hundred eyes of Argus, not the single eye of the Cyclops.

This volume is published by Barrington Stoke, who specialise in books for people with dyslexia and reluctant readers. As such, the book is short (just over a hundred pages), has clear, large type, no text justification, and simple language. The language is simple, but the story is not dumbed down in any way – so it’s ideal for teens who might struggle with 400-page YA adventures, but still want mature, exciting reads.

It’s a nicely-produced volume, too, with a striking cover (illustration by Paul Young) that should appeal to readers looking for any one of “War, Ancient Rome, Girl Power,” as the tags say on the back cover.

It’s a book I thoroughly enjoyed, and it made me dig out my old translation from the bottom of my bookcase and re-read Book XI. Who knows? It might encourage other people to read Virgil, and that can only be a good thing.