Phoenix, by SF Said, with illustrations by Dave McKean, is a science-fiction adventure of galactic scale.

When I was a kid, more decades ago now than I care to remember, science fiction made up a significant proportion of my reading. Eleanor Cameron’s The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet was my comfort re-read – I read it over and over again. Astronomer and TV personality Patrick Moore wrote a series of six near-future semi-realistic books – the Scott Saunders Space Adventures – that had pride of place on my shelf right next to my HMSO guide to Moon, Mars, and Meteorites. Doctor Who novelisations sat in stacks on my bedside table to be devoured one after another. (My record was seven in one day.) The Star Wars novelisations and spin-offs, too, found their way onto my shelves – my dad bought me a copy of Star Wars before we’d even seen the film, and I have a vivid recollection of reading the back of the book on the bus home and asking him what a lightsaber was! I frequently searched out Andre Norton books from the library. Adult scifi writers like Robert Silverberg (Revolt on Alpha C) and Robert Heinlein (Have Space Suit, Will Travel) wrote what they called “juveniles” that provided a gateway into the world of grown-up scifi that I gladly followed just a few years later. John Christopher, too, wrote for children – his Tripods series had me rivetted.

At the time, it seemed like half of all children’s books were science fiction. That probably wasn’t true in general, but it was certainly true of my bookshelves, and I definitely never had any problems finding science fiction when I wanted to read it.

I’m not sure that’s the case these days. Young Adult has its science fiction contingent, but a lot of that is dystopian, which I’d regard as a separate sub-genre. But children’s books these days are dominated by contemporary and fantasy stories, which means that it’s always a great pleasure to come across a really good children’s scifi book.

Perhaps the greatest modern master of children’s science fiction is Philip Reeve, whose Railhead was my top book of last year.

But Phoenix gives Railhead a run for its money.

Lucky thinks he’s a normal boy, but when he starts to dream that the stars are singing to him, and wakes up with scorch marks on his bedsheets, he begins to suspect that there’s something else inside him. His mother insists that to protect Lucky, they have to run – far away. Off-world.

Their escape doesn’t go to plan, and when things go horribly wrong, Lucky finds himself on the Sunfire, a ship crewed by aliens – the Axxa, the very species that the Humans are at war with.

They take Lucky on a journey across the galaxy and beyond, to search for his father, to find the limits of what makes him so strange, and to understand the connections that bind us all.

The scale is huge, operatic, and galaxy-spanning, and the stakes get higher and higher until the Human/Axxa war threatens the entire galaxy; but it’s an intensely human story too, with Lucky coming to terms with the fact that the propaganda he’s been fed all his life may not be entirely accurate, and that the Axxa aren’t so different from Humans. And not just on a philosophical or political level, but on a deeply personal level, too, as Lucky comes to know and love the crew of the Sunfire.

The relationship between Lucky and Bixa, the quick-tempered Alien warrior with needles in her hair, forms an important arc, and is emblematic of Lucky’s growing understanding of the connections that make life worth living. The horrors of war, and the frustration with leaders who see the deaths of innocents as acceptable to further their aims, are nothing compared to the Living Death, a form of soul-crushing depression caused by the weapons of war that strips away all of your humanity and cuts you off from everyone you might love – and you can take that as a metaphor if you like.

There’s a strong undercurrent of mysticism in Phoenix, an almost mythological tone in places that meshes closely with the science-fictional elements like dark matter and starships and space pirates without jarring.

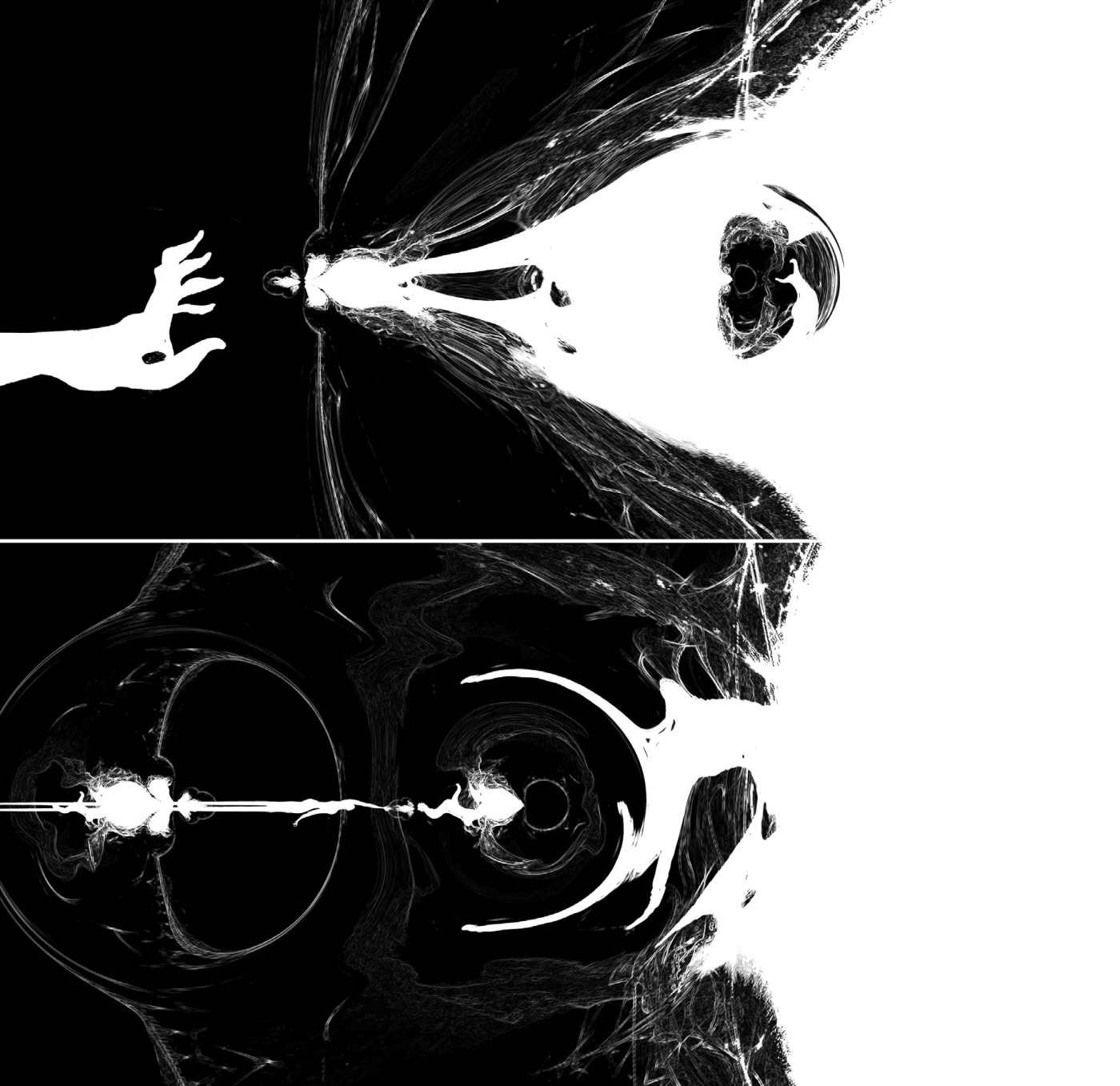

And that mystical element is emphasised beautifully by Dave McKean’s spectacular illustrations. McKean doesn’t bother with illustrating the mundane day-to-day action of the plot, but restricts himself to the cosmic, the spaces between the stars, and the journeys within Lucky’s mind.

The illustrations provide a richness to the book, an extra layer of cosmic wonder.

Which is perfect, because this is a book of cosmic wonder. Famously, SF Said takes his time writing his books – Phoenix took him seven years. If this is the result, then all I can say is – take your time, Mr Said. It’s worth the wait.